History of Parliamentarism in BiH

Period of Austro-Hungarian rule

After the Berlin congress held by the Major Powers on July 13, 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina fell under temporary Austro-Hungarian occupation, while the Sultan’s sovereignty was formally retained.

(Monographs of the "Parliamentary Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the 2010 edition.)

O From 1908 to 1918, contrary to the terms of the Berlin Congress, Austro-Hungary formally annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina. More than 15 months passed from the time of the declared annexation – which was justified by the need to establish the Constitution and democracy in the political sphere through the introduction of the Council – before the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina was enacted. After lengthy preparations and constitutional polling, on February 20, 1910 the National Constitution (Statute) of Bosnia and Herzegovina was declared. The statute guaranteed all citizens equality before the law. Although the constitution was rather restricted and did not provide the local population and institutions with much power, as supreme administration remained in the hands of the Joint Ministry of Finance in Vienna, it had indisputable importance in marking the beginning of the constitutional system in our country. It introduced three new institutions to the political sphere of the country, of which the Council (orig. Sabor) was certainly the most important. Regardless of its restricted legislative rights, the Council was an institution necessary for addressing and resolving contemporary important issues. It was empowered to cooperate in dealing with issues which, under the law on the administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, did not explicitly fall within the competence of the Austrian and Hungarian Parliaments. Through the enactment of the constitution and the commencement of the functioning of the Council, the development of the constitutional and legal system in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the period of Austro-Hungarian rule was completed.

The restrictions imposed on the Council were multiple. The Council could not independently propose and enact laws, and it could not even discuss certain matters. The National Government did not report on its work to the Council, nor did the structure of the Government depend on the Council. On the other hand, the Government depended on this representation in terms of its available funds, because the annual budget depended on the Council. Although the Council could not independently decide on the most important issues to the country and its people, the declarations of some representatives on the Council could reflect the aspirations of the social groups they represented, which the Austro-Hungarian authorities took into consideration.

Although in 1907 the curia principle in Austria was abandoned as inefficient and universal suffrage was introduced instead, the Bosnian Council was based on the confessional and the curia principle due to its specific circumstances. It had 20 delegated members and 72 elected representatives. Any of the three confessions gave five delegated members to the Council each, while Jews were given one delegate vote. Delegated members of the Council were as follows: Reis-ul-ulema, the principal of Muslims’ land holdings, the Muslims’ regional leader from Mostar and Sarajevo, and a regional leader who was elected first, four Metropolitans, the Vice-President of the Grand Administrative and Educational Council of the Serb Orthodox Church, the Roman-Catholic Archbishop, two provincials of the Franciscan Order, a Sephardic rabbi of the higher order of Sarajevo, the President of the Supreme Court, the President of the Sarajevo Chamber of Attorneys, the Mayor of the City of Sarajevo and the President of the Sarajevo Chamber of Commerce. Pursuant to the election laws, the population was divided into three curiae.

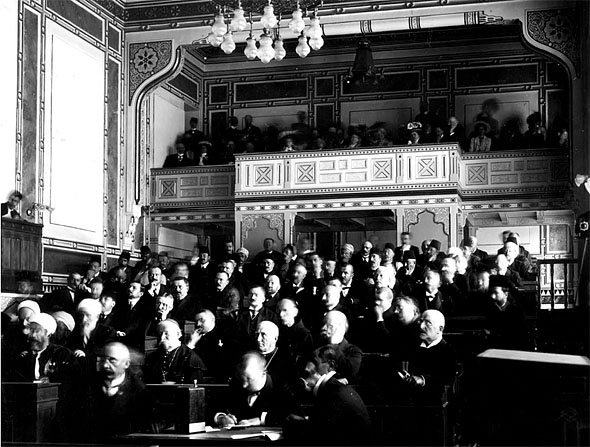

Opening of the Assembly of Bosnia and Herzegovina

The first curia included all those who, by virtue of their landed property, general tax liabilities or education belonged to a special social group of the population. It included Muslim landowners, begs and agas (lower landed gentry), rich merchants and industrialists, graduates and military officers. It held 18 seats in the Council. The second curia included the urban populations of places having the status of town or governed by the law of March 21, 1907, and which did not belong to the first curia. This curia had 22 seats in the Council. The third curia encompassed the entire rural population belonging neither to the first nor second curia. This curia held 43 seats. According to national confessional groups, the Orthodox held 31, Muslims 24, and Catholics 16 seats, while Jews held one seat (in the second curia). The Council Presidency was not elected by representatives. Instead, it was appointed by the emperor. The government functioned absolutely independent of the Council, which was entitled only to file petitions to the National Government.

After the elections, including those regularly held in May and subsequent ones in September 1910, four political parties entered the Council. All Orthodox mandates were given to the Serbian National Organization (31), all Muslim mandates were given to the Muslim National Organization (24), while the Catholic mandates were split between the Croatian National Community (12) and the Croatian Catholic Association (4). With regard to the social structure of the Council, intellectuals (45) and landowners (24) were predominant. Several well-known cultural and public figures of that time were also elected to the Council. For example, the writer Svetozar Ćorović, Ali-beg Firdus, one of the most prominent leaders of the Bosniak-Muslim Movement for Autonomy, the Archbishop dr. Josip Štadler, Petar Kočić, a Serb cultural, national and political figure, Safvet-beg Bašagić, a cultural figure, dr. Nikola Mandić, dr. Jozo Sunarić, dr. Murad Sarić, dr. Nikola Stojanović, dr. Jefto Dedijer, dr. Mustaj-beg Mutevelić, dr. Milan Srškić, and Šerif ef. Arnautović, among others.

Although they were not members of the Council and did not participate in voting on occasions when certain legal grounds were established, representatives of the National Government were an important factor in the work of the Council and their standpoints frequently directed Council discussions, including the passing of certain proposals and laws. The National Government was assigned this important role by the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, which prevented the Council from controlling its work. After the May elections, the country was visited by the emperor Franz Josef.

On that occasion, he issued a Patent on May 31 and convened the Council session for June 15, 1910, which was held on that day. The first president of the Council was Ali-beg Firdus, while Vojislav Šola and dr. Nikola Mandić were Vice-Presidents. Since Ali-beg Firdus was on his death-bed, Vojislav Šola acted as the Council President throughout the first session. Later Safvet-beg Bašagić would be appointed President of the Council. The opening of the Council session was followed by the unsuccessful assassination of General Marjan Varešanin on the Emperor’s Bridge (orig. Careva ćuprija), on his way back from the opening ceremony. The would-be assassin, a Serbian youth named Bogdan Žerajić, committed suicide to prevent an investigation.

At the beginning of the Council’s work, all representatives mainly acted jointly and in unison towards the National Government regardless of the political parties to which they belonged. They wished for the Council to be used within its existing authorities for bettering the political and economic situation in the country. A joint request of representatives followed, demanding the Council’s Constitutional powers to be expanded by the resolution of June 23, 1910. The representatives also worked in concert on some specific issues, such as the abolition of the prohibition on holding literacy courses, requests for the railway inscriptions not be written in Hungarian, the abolition of the German language in internal communication, a new law on forest fines to be enacted thus considerably improving the situation of peasants, among other issues. The conflicts in the Council broke out during the discussions on the draft law on the postal savings bank in late 1910 and early 1911, and raising the land question in the Council definitively put an end to cooperation, resulting in the splitting of representatives into factions each looking for allies among the political groups in the Council. This also put an end to efforts by the National Government to create a “work majority” comprising representatives from all three religious-ethnic groups. During the four sessions, the Council discussed a number of issues related to laws submitted to the Council at the initiative of either the authorities or the representatives themselves. Because every year the government proposed a budget which exceeded the one from the previous year, the right of the Council to vote on this issue effectively constituted its most extensive power as defined by the Constitution. As a result, representatives made efforts to connect voting in favor of laws that were important to them with their budget votes. Still, the most important issues addressed by the Council were those related to the land question and landed property in general, which were the major issues raised at the first and fourth sessions, as well as the language issue, a key part of the national issue, both of which reflected the ethnic relations in the representative body. The Bosnian-Herzegovinian National Council became a theatre of frequent discussions on the land question. The three major groups split based on religiousethnic identity, while the fourth participant was the National Government and its representatives at the Council sessions. It should be noted, however, that the major battle was fought between the Bosniak 1and the Serbian representatives, as the landowners were generally Muslims and the tenant peasants/serfs were predominantly Orthodox. At the first session, the groups presented their arguments in favor of the most desirable method for resolving the land question, raising the issues of terminology and other essential questions in this context – what the land question referred to, whether a tiller of the čifluk (a type of feudal holding under Ottoman rule) land is a serf or a tenant peasant, the origin of the Orthodox and the Muslims in Bosnia and Herzegovina and which group existed earlier in Bosnia and which one, as a consequence, was more entitled to the land, whether the relation between the landowner and the tiller is of a private-legal or public-legal character, the motives of the Austro-Hungarian administration in initiating external colonization – to strengthen agriculture or to weaken the Serb ethnic compactness in certain regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina – as well as other issues related to the land question.

The ‘’Konak’’ residence was a seat of the Governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Austro- Hungarian administration. ‘’Konak’’ remains a residence today

At the second session they elected the Council Boards, discussed the language issue, roads, irregularities in leasing the Tuzla saltworks, and the budget, which was rejected at the second session. They also criticized the police force applied during the pupils’ demonstrations against the governor Cuvaj and the introduction of a Commissariat in Croatia in front of the Sarajevo Cathedral. Since the Government was in conflict with the entire Council, it decided to close the second session.

During the period from 1912 to 1914, the state official policy predominantly tackled the railway building issue in Bosnia and Herzegovina and strived to secure support for its investment programs from all the groups in the Council. Apart from this, the language issue was the focus of all Croatian-Serbian discussions and conflicts. There was also some restructuring among the political parties.

At the inter-party conference on June 10, 1912, the newly appointed joint Minister of Finance, Leon Bilinski, presented his investment program demanding and expecting absolute support. As the majority in Government decided to adopt the program with certain amendments, Bilinski stated that he would implement the investment program without the Council’s support. Still, after being somewhat agreed on accepting the entirety of the Minister’s investment program and voted in favor of the budget, thus satisfying the requirements for convening the third session of the Council on October 22, 1912. Expectedly, despite obstructions by the opposition, the budget and the unchanged Law on Railways passed.

It was then that the language crisis broke out, as it was one of the most important issues concerning the national question. At the time of the Council, the language issue in internal political relations pertained to defining the name of the language and the use of the alphabet, though not the essence of the language. Despite the different approaches to the language issue by the ethnic-political groups in the Council, the agreement was finally reached in 1912 after the Croats conceded and allowed for the language to officially be named Serbo-Croatian. The problem remained of how to resolve the language issue with the Government, which has ever since been given primarily social and economic dimensions.

With the intention of resolving the language issue in their own interests, local political figures made efforts to connect this issue with resolving other issues under dispute upon which the authorities attempted to agree within the Council. In particular this referred to governmental strategic investment programs and the budget, the passing of which the representatives tried to connect with resolving a range of their own demands. With regard to voting in favor of the Law on the Building of New Railways (November 1912), all Council groups requested that the Serbo-Croatian language be legalized as the external and internal official language used in the railway sector. Although the Law on the Building of Railways passed owing to the votes of the “work group,” the Council influenced voting in favor of the Government’s 1913 budget proposal making Serbo-Croatian the only official language. Having realized that the Council would not vote in favor of the 1913 budget without having the language issue resolved in the spirit of the representatives’ demands, the Austro-Hungarian authorities adjourned the Council session (December 18, 1912) indefinitely. The session did not continue; instead, it was formally closed at the time of the Skadar crisis on May 4, 1913. On May 3, 1913, during the international crisis caused by the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum requesting Montenegro to withdraw its forces occupying Skadar, in fear of the reactions of Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the authorities imposed special measures on the country and suspended the eight most important Articles of the Constitution. When the Montenegrin army withdrew from Skadar on the May 15, the special measures were rescinded as well.

At the time of the Skadar crisis, the group associated with the Serbian Word found itself in a difficult situation between the authorities and the Serb public, and 12 representatives within this group renounced their mandates in consequence. At the subsequently held elections, the vacant positions were mainly occupied by the candidates of the progovernment, newly established Serbian National Party of the lawyer Danilo Dimović (acquiring nine seats), by which the requirements were met for the fourth and last session of the Council, which was to be held on December 29, 1913. In the summer of 1913, once the problems in forming the “work majority” were overcome, a compromise was reached on the Law on the Official and Teaching Language. The new governmental coalition (Muslim and Croatian Council caucuses and the Serbian group of Danilo Dimović) and the National Government agreed that the use of Serbo-Croatian language should be enabled in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the internal railway services, provided that military interests allowed it. Having received consent from the Hungarian and Austrian governments that the law on language would be enacted, the pro-government Council majority voted in favor of it once the Council was reopened on December 30, 1913. Once this law was sanctioned, Serbo-Croatian was introduced into all administrative bodies of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the exception of the national railways, where German retained its primacy for military-strategic reasons.

During this relatively peaceful session, the land question was raised again, as was the issue of the representation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the common delegations, including the issue of the name and use of the official language. In the first half of 1914, several important draft laws on investments were adopted. This was also a period of turbulence in the governmental Council majority among all three ethnic groups.

The Council’s activities were discontinued due to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne, by Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914 in Sarajevo. Soon after the assassination, the fourth session of the Council was formally closed on July 9, 1914. On July 28, Austro-Hungary declared war on Serbia, commencing World War I, and on February 15, 1915, the Emperor abolished the Council. The events following the assassination prevented the sanctioning of some laws adopted by the Council and the implementation of those enacted for which even the necessary funds had been obtained.

Analysis of the attitudes towards the issues raised in the Council and the relationships between the groups of representatives clearly indicates the manner in which the local political forces accepted parliamentarism. The existence of the Council and its activities enabled the ongoing development of national political organizations into modern political parties, demonstrated through the work of this parliamentary body. Through its work, it is possible to monitor numerous issues and relationships, the land question and internal political movements in particular, including the inter-ethnic relations in Bosnia during the Constitutional period. The work of the political parties based on mutual agreement and the options in the Council had a positive impact on social movements, while disagreements between the political parties and their dissident groups negatively affected the country’s stability and relations among the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

– Doc. dr. Edin Radušić

1: While writing this text we faced a dilemma as to which expression to use for the Bosniak-Muslim population and their political representatives: Bosniaks or Muslims? Considering that all the sources at the time refer to them as Muslims and all their institutions have the prefix Muslim and that, on the other hand, the current denomination for that ethnic group is Bosniaks, we decided to use a combination of the two, given that Muslim is used when referring to institutions and phrases from the original sources, while Bosniak is used when referring to groups or individuals as part of the ethnic group. (author’s observation)